I write this text not as a review of the 2015 Istanbul Biennial, but rather as a series of thoughts and questions that arose after my recent visit to the Biennial as part of a wider ongoing body of research on biennials in general. While the main focus of my research is actually the Berlin Biennale, taking a moment to step out of my imaginary Berlin of the past and think about biennials in urban environments more generally by actually experiencing one was a welcome breath of fresh air that brought new perspectives to my work. This was my second visit to Istanbul, my last was in 2013 for my participation in an Independent Curator’s International (ICI) Curatorial Intensive, where conducted field research on the 13th Istanbul Biennial. Revisiting the site two years later no only allowed me to return to many of the concepts I originally grappled with back in 2013, such as locatedness, it also allowed me to think more concretely (and concrete is really the right word in Istanbul’s case) about the relationship between contemporary art exhibitions in urban space, and about temporality and curatorial approaches to it.

I write this text not as a review of the 2015 Istanbul Biennial, but rather as a series of thoughts and questions that arose after my recent visit to the Biennial as part of a wider ongoing body of research on biennials in general. While the main focus of my research is actually the Berlin Biennale, taking a moment to step out of my imaginary Berlin of the past and think about biennials in urban environments more generally by actually experiencing one was a welcome breath of fresh air that brought new perspectives to my work. This was my second visit to Istanbul, my last was in 2013 for my participation in an Independent Curator’s International (ICI) Curatorial Intensive, where conducted field research on the 13th Istanbul Biennial. Revisiting the site two years later no only allowed me to return to many of the concepts I originally grappled with back in 2013, such as locatedness, it also allowed me to think more concretely (and concrete is really the right word in Istanbul’s case) about the relationship between contemporary art exhibitions in urban space, and about temporality and curatorial approaches to it.

*******************************************************************************

“What did you think of the biennial?” everyone kept asking me. To be honest, after my first day in Istanbul, the biennial itself wasn’t really what I was thinking about. Before setting out to see the biennial, I was having breakfast with a friend when she found out that there had been two suicide bomb attacks at a peace rally in Turkey’s capital of Ankara. One hundred and two people died. At the time of writing, those who committed this horrendous act of violence are still to come forward however the Turkish government have blamed ISIS.

After receiving this information I travelled through the biennial in a fog; my enthusiasm for experiencing new artworks in their urban settings was quickly overshadowed by a feeling of fear and sadness. How on earth could I possibly look at artwork, engage with curatorial themes or even enjoy the biennial experience knowing that so many people had just died? I remembered having a similar feeling during my last visit to Istanbul in September 2013, a week or so after the opening of the 13th Istanbul Biennial. The situation was surreal: only a few months after seeing violent images of the brutal police reaction to the Gezi Park protests, there I was only a 10 minute walk away from where it all happened, sitting in a chic cultural institution in discussion with Fulya Erdemci and Andrea Philips about how they had negotiated with protesters who had several times interrupted the biennial’s public programme.

As it was the last time I was in Istanbul, I again began to feel increasingly sceptical about the biennial’s ability to deal with a key part of urban life: temporality. The question that I always seem to come back to when thinking about biennials taking place in urban space is: how can the biennial’s curatorial team ever truly curate exhibitions for the future? Temporality plays a central role in the identity of all cities, and in the case of cities like Istanbul where it takes form through rapidly changing urban, political and social situations, such ambitious and complex curatorial intentions as those found in biennials seem out of step. How does the biennial learn to bridge the widening gap between the curatorial intentions of the biennial and the lived experience of it in the present?

Leaving that question aside for now, perhaps the best way to proceed is by examining what I perceive as three curatorial intentions of the 2015 Istanbul Biennial’s as they relate to the spacio-temporal structure of their urban context. Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev’s curatorial framework, is an impressively complex, if somewhat esoteric, theoretical proposition:

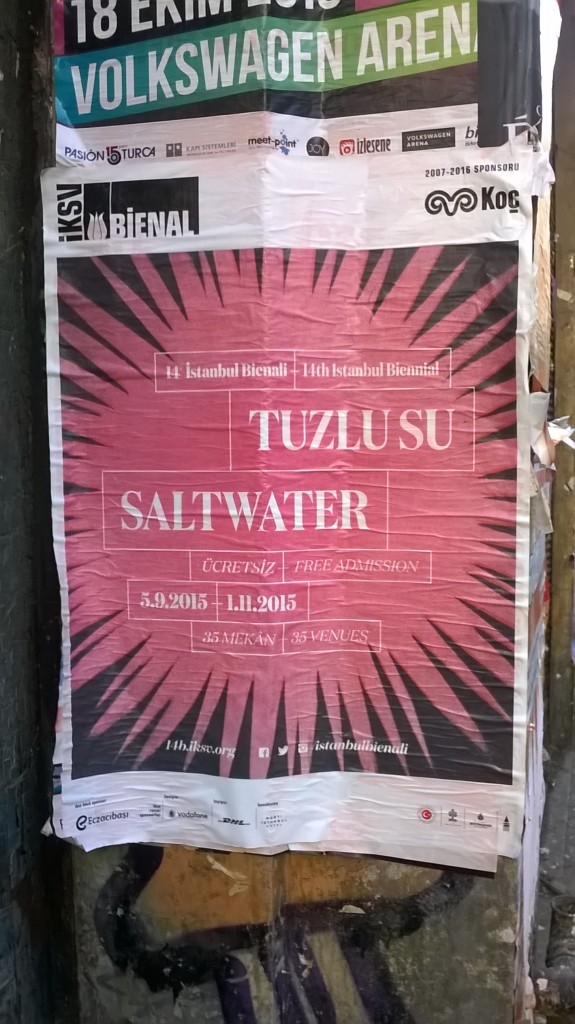

“SALTWATER: A Theory of Thought Forms hovers around a material– salt water – and the contrasting images of knots and of waves. It looks for where to draw the line, to withdraw, to draw upon, and to draw out. It does so offshore, on the flat surfaces with our fingertips but also in the depths, underwater, before the enfolded encoding unfolds.” (Christov-Bakargiev, 2015)

The first intention that is made clear by Christov-Bakargiev is for the biennial audience to physically experience the city and the saltwater running through it in the form of the Bosphorus River. The biennial is positioned as a healing, transformative experience for visitors as they travel through the city:

“This city-wide exhibition on the Bosphorus considers different frequencies and patterns of waves, the currents and densities of water, both visible and invisible, that poetically and politically shape and transform the world. With and through art, we mourn, commemorate, denounce, try to heal, and we commit ourselves to the possibility of joy and vitality, of many communities that have co-inhabited this space, leaping from form to flourishing life.” (Christov-Bakargiev, 2015)

With more than 80 artists exhibiting work in more than 30 different locations spread far and wide across the city, with most locations featuring only one artist, Christov-Bakargiev demonstrates her second curatorial intention for the city itself to be viewed as an artwork itself. Certain districts along the Bosphorus have been selected in accordance with their geographic proximity to the sea, thus reinforcing her Saltwater theme. In biennial paraphernalia such as the biennial travel guide and the (rather illegible) fold out map, the unnecessary parts of the city are edited out, much like the selection of artworks for an exhibition. Each district and biennial venue, whether a private residence, a school, car park, hotel room or warehouse is featured in the Biennial Guide with accompanying historical information, much like the artist biographies we are familiar with seeing displayed next to contemporary art works in exhibitions.

Christov-Bakargiev’s final intention is to be seen as a legitimate contributor to and commentator on the city of Istanbul through her personal connection with certain places there. With biennials such as Istanbul and Berlin that share a focus on taking the city itself as a starting point for the development of a curatorial framework, the need for the curator to connect with their immediate surroundings, is an important part of the curatorial process. The curator (or curatorial team) is invited to live in the city of the biennial, and based on their social, political, and geographical lived experiences of that city, determine their curatorial position, develop their framework and select or commission artists for a series of exhibitions. In Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev’s case a desire to be seen as having an emotional connection with the city, is displayed alongside her selected artworks at venues such as The Greek School, Istanbul Modern and Arter, where her group shows can be found. Her exhibition introduction texts come complete with a date and location – presumably where they were written – inviting us to conjure up images of a meditative curator standing in an imagined urban space, inhaling briny seawater as she contemplates contemporary art. It’s as if the exhibitions, are intended to serve as documents of a past time and place that we imagine from our present position.

These three intentions suggest that it’s not simply enough anymore to select artists who focus on the urban within their work. Christov-Bakargiev’s biennial arrives at a time when ‘curating the city’ is a well-established curatorial practice, perhaps exactly because, unlike the white cube gallery, the proliferation and dominance of the metropolitan biennale model allows this. But what is it about these particular urban landscapes, cities like Istanbul and Berlin that through urban development projects are caught in a perpetual state of “becoming”, that curators are so eager to curate and for us to traverse? What exactly is the image the curator wants to conjure? Is the city imagined for us as a complex socio-geographical-political structure or is it merely an interesting backdrop that lends a certain gravitas to an artwork? Is it imagined as a history lesson we must read through the urban fabric, through the layers upon layers of, sometimes violent, history embedded in the walls, streets and interiors? Is it imagined as the city-to-be contained in the voids or the in-between non-spaces left behind by decay, demolition or ruin? Or is it imagined as an inaccessible or undesirable space only rendered desirable and accessible once the curator reveals it and leads you down a side alley, through a door and down some crumbling steps?

One thing is for certain: it is simply not enough anymore to reveal the contemporary (and by that I mean a representation of our present times) through art production alone; the urban context must be curated and exhibited too. If this is the case, and if the city is then on display inasmuch as the artworks, that means that visitor experience of the biennial becomes incredibly significant. However, like all curatorial intentions of biennial exhibitions, Christov-Bakargiev’s may never be fulfilled. Audiences will never be able to totally view the biennial in exactly the way that the curator intended nor can the curator expect that they ever could. I don’t believe that Christov-Bakargiev expects us all to be fully able to experience the saltwater (I certainly never even managed to smell it, let alone get near it when I was there), nor view the city as an artwork (again, all I was able to see was the Beyoglu district) nor connect with her personal experience of the city. Cue the return to my original question: how does the biennial learn to bridge the widening gap between the curatorial intentions of the biennial and the lived experience of it in the present? How can these intentions embedded in curatorial frameworks developed over the course of a curators two-year residency preceding the biennial’s opening, ever relate to the present situation in which it is experienced? Is it even possible? Or in other words, how can the temporality of a city be dealt with curatorially?

References

Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, 14th Istanbul Biennial website http://14b.iksv.org/theory.asp#english as sited at 29th October 2015.

This essay was first written for the Contemporary Art Exchange blog on the 29th October 2015 and can be found here: http://contemporaryartexchange.org/curatorial-intentions-and-the-temporality-of-urban-space/

There are currently no comments on “Curatorial Intentions and the Temporality of Urban Space”. Perhaps you would like to add one of your own?