The conference began rather promisingly with an impressive line-up of international curators and directors of biennials world-wide and the encouraging title of Biennials: Prospects and Perspectives. As illuminating and inspiring the presentations on the various biennial models were, I felt the conference as a whole failed to deliver on its promise to “sound out the potential of such large scale events following almost three decades of Biennalialisation”.[1]

The conference was a part of the ongoing exploration of biennials through ifa’s (Institute of Foreign Cultural Relations) Biennials in Dialogue conference series – one is left to guess that the superficiality of the discussion that took place at this event may be a result of the fact that more in depth discussions had already taken place at previous events. However, I believe the lack of critical discussion that the event would have otherwise benefited from was due in part to the conference format that favoured slick presentations over critical discussion. To be fair, most curators and directors gave honest responses when questioned about the challenges involved in organising biennials. However, the lack of in-depth discussion was not helped by the fact that most presentations ran longer than they were meant to, giving both the panel moderators and responders (and I’m still not sure why the felt the need to have both of these) very little time to engage in meaningful dialogue with the speakers and audience members.

The conference began with a keynote speech by Ute Meta Bauer who introduced the five main themes – Biennials and Public Space, Biennials as Motor for Social Change, The Dynamics of Biennials and the Role of its Actors, Chances and Limitations of Biennials in the Context of Marketing and Policies and Alternatives/Open Spaces. Meta Bauer illustrated today’s need for such a conference by suggesting that there was a climate of biennial fatigue in the West contrasted by more dynamic cultural production either contributing to or in spite of great political change taking place in Asia and Africa. She declared that increasing urbanisation and cosmopolitanism due to globalisation needed to be addressed by biennial curators and directors and that it was important to include other intellectuals engaged in non-arts discourse in the debate surrounding biennials.

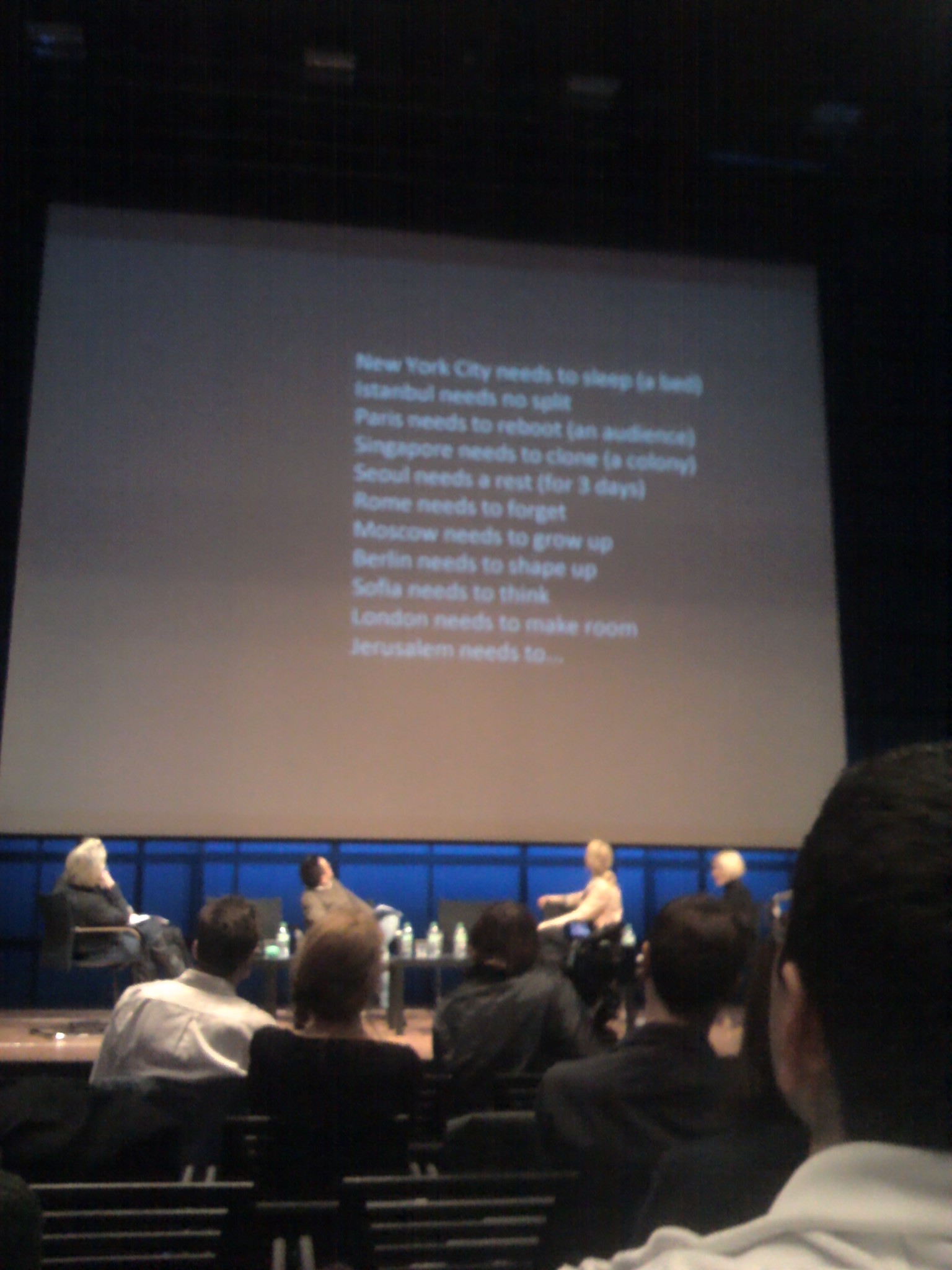

This last suggestion was somewhat curious, given that there were really only two perspectives presented at the conference – that of the biennial curator, and that of the biennial organiser or director (with the possible exception of biennial-exhibiting artists such as Christoph Schäfer and Luchezar Boyadjiev, who also occasionally assume the role of curator). The presentation of these two perspectives was useful for differentiating between approaches in biennial making, such as the challenges inherent in curating just one edition of a biennial versus the long term work involved in developing and sustaining a biennial for a city and its citizens, particularly within various geo-political contexts. However, the structure of the conference wasn’t open to voices without a direct stake in the biennial system, voiced from those who could potentially offer a distanced, critical perspective. The panels on Biennials and Public Space and Biennials as Motor for Social Change were designed to explore the notion of art in the public domain, new definitions of publicness and the impact of biennials on transforming societies and politics – a perfect opportunity, I would have thought, to bring in outside voices such as members of the public, politicians and activists to contribute to evaluating a biennial’s “success” in this role.

Further questions Meta Bauer introduced during her keynote speech regarding the future prospects of biennials were also left unanswered over the course of the three days. Understandably difficult questions, such as the future financing and the increasing numbers of biennials and decrease in public finding for the arts, how to deal with government and other influential agendas, or whether we even need biennials, may well be completely unanswerable. However, despite Meta Bauer’s insistence on the urgency to discuss ways of sustaining biennials (especially in light of the escalating pressure on the Sydney Biennial to drop their sponsor Transfield Holding – which was happening at the same time as the conference), the organisers failed to provide an appropriate platform in which speakers could engage fully in discussing this theme. It wasn’t until the last two panels on the final day that this issue was raised again – but as with the previous presentations, very few speakers actually offered their opinions or dared suggest alternative models for funding structures.

Adding to the oversight of addressing such a topical issue was the way in which conference organisers and speakers engaged (or didn’t) with the statement sent by Sydney Biennale CEO Marah Brae, absent due to her need to deal with the threat of and increasing likelihood of artists boycotting the Sydney Biennale. The letter itself was disappointing enough. It seemed an uncompromising and unapologetic attempt (written before Transfield Holding Director Luca Belgiorno-Nettis resigned from the Sydney Biennale Board of Directors) to garner support from international colleagues far removed from the reality of the situation unfolding in Australia. The statement seemed to jar with Ute Meta Bauer’s comments on Sydney in her opening speech, which applauded several artists’ decision to withdraw from the biennial. Nonetheless, no discussion surrounding other curators’ or directors’ opinions on the matter took place – let alone suggestions for potential solutions for similar crises. While the conference organisers did attempt to juxtapose the statement from Marah Brae with the reading of part of a counter response to the Biennale’s initial response by Melbourne University scholar Nikos Papastergiadis, there was no questioning of how long the biennial organisers knew about Transfield’s contract to serve Australian Government off-shore detention centres, no explanation as to why it took them so long to respond to public concern, nor what kind of dialogue they’d had with artists regarding the issue. The feeling I got was that the whole issue was a little too hot to touch, and/or that nobody wanted to rock the curatorial boat.

Despite these disappointments, there were moments of inspiration amongst the three days of the conference. Blair French offered short but delightfully insightful responses to the panel on Biennials and Public Space questioning whether producers of biennials legitimise bureaucratic or government agendas. And if not, whose agendas are curators and directors addressing? Rather poetically, he described the biennial in terms of its rhythm of absence, presence and withdrawal – something that is experienced long after its finished – and expressed his desire to explore how biennials create new locales and who exactly is involved in this process.

In the panel on Biennial as Motor for Social Change, Gerardo Mosquera contributed some interesting perspectives on the development of future biennials. Borrowing a phrase from the artist Mike Kelley, he suggested that public art showings should not be passive aggressive, but move from the city towards art, rather than use the city as merely a scene or a setting. Mosquera argued, curators should move away from blockbuster shows towards multiple, smaller events and trigger contemporary art’s potential to move beyond itself.

Personally, I would have loved to hear much more from the other speakers participating in this panel. Particularly inspiring were Patrick Mudekereza’s reflections on the Biennale le Lubumbashi, which he runs in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Mudekereza described how this new biennial strives for independence, searches for ways to look at their own history without the colonial gaze, and constantly questions their own legitimacy and their identity. With no budget, problems obtaining ethical funding, and operating without a clear knowledge of the agendas of government agencies, the biennial was presented as an example of a bottom-up, rather than top-down curatorial approach and as a tool for citizens to reimagine their city.

The topic of the discursive or educational turn within biennial making is another fascinating area of development that I felt could have been discussed in more depth after the presentation by speakers such as Monica Hoff, curator of the Cloud Formations section of the Bienial do Mercosul in Porto Alegre. She demonstrated how education and learning can be used not just as an add-on or a theme within biennial curating, but as the core activity of developing and sustaining the biennial within a small and remote community. Hoff described the Bienial do Mercosul as a biennial owned by the community and thus positions the community as both its main cultural contributor and critic.

Finally, the Alternative/Open Spaces panel proposed important questions for new and emerging biennials in developing countries such as Paraguay and Haiti. It seemed the curators pioneering these projects, namely Royce Smith and Leah Gordon respectively, were eager to have feedback from their peers and the audience on issues such as: how do you avoid playing into the academic discourse surrounding poverty tourism? How do you manage both international and local expectations when you’re providing a platform for people who just want a voice? Smith’s comments provided a fitting final contribution for the close of the conference with a humbling reminder that above all else, biennials need to be honest, forthright and engaged and that while a biennial can be the starting point and an argument for investing in a city’s arts infrastructure we should never forget that biennials can damage or drain already existing local arts scenes.

Perhaps these ideas can be returned to in the next edition of Biennials in Dialogue, with the addition of other voices that can offer yet more diverse perspectives and offer much needed critique of the way in which curators and directors instigate, curate and manage biennials.

by Kate Martin

[1] Buddensieg, Andre and Aus dem Moore, Elke, Biennials: Prospect and Perspectives, conference handout, February 28th, 2014, ZKM, Karlsruhe

There are currently no comments on “A non-biennial curator’s perspective on the “Biennials: Prospects and Perspectives” conference at ZKM, Karlsruhe Feb 27-March 1, 2014”. Perhaps you would like to add one of your own?